Today is Leonard Bernstein‘s 100th birthday. Bernstein is one of my favorite composers so I have really enjoyed the attention to his music during his centennial. In the past year I’ve heard two performances of Candide in San Francisco and Santa Fe, my first-ever experience of Trouble in Tahiti at Opera Parallèle, and a splendid version of Arias and Barcarolles which has just been released as a digital recording from the San Francisco Symphony.

My favorite work of Bernstein’s – yes, even more so than West Side Story – is his Mass: A Theatre Piece for Singers, Players, and Dancers. Seeing the recent commentary about Mass and other Bernstein compositions during the centennial struck me as very interesting. It has been a great way to see what writers share my sense of what is important in art and music, and which writers have a perspective totally opposite to that.

I had a somewhat unusual introduction to this piece. Gordon Hallberg, the director of the MIT Brass Ensemble when I was a graduate student, made a brass ensemble arrangement of excerpts from the piece that we performed at a concert. Hearing the music divorced from the words and staging, I wondered what was this beautiful music and why hadn’t I heard it before?

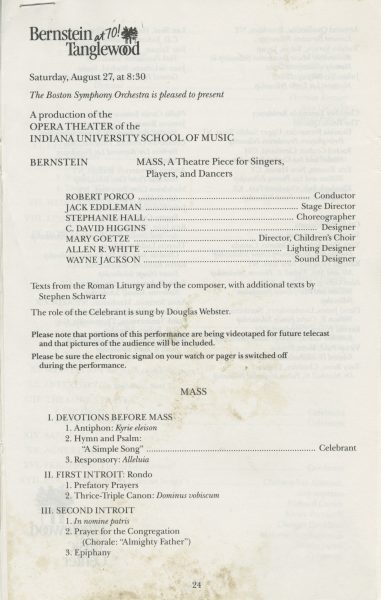

I eventually heard the original cast recording but it didn’t move me as much as I had hoped. Things changed when I got to see two performances in the course of six months. The first was the Indiana University Opera Theater performance with Douglas Webster as the Celebrant, done at Tanglewood in August 1988 as part of the Bernstein at 70 celebration.

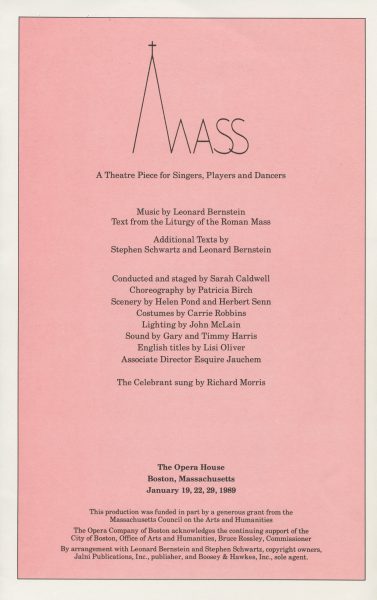

The second was Sarah Caldwell’s fully staged production at the Opera Company of Boston in January 1989, with Richard Morris as the Celebrant.

After seeing those two performances I was absolutely and completely hooked on this marvelous work.

When I saw the article in the San Jose Mercury News that the Cabrillo Festival of Contemporary Music was doing Mass in August 1999 and auditioning for a chorus – the day before I left for a business trip – I made sure to call them from the road so I had an audition waiting when I got back. I got the gig and sang in the Choir for 3 performances conducted by Marin Alsop, The production was directed by Douglas Webster who again played the Celebrant. The Street Chorus was packed with amazing local singers, including Lori “Bob” Rivera (singing World Without End) and William Neely (singing Easy). I purchased the vocal score to Mass in advance of our rehearsals and it remains one of my most cherished scores, even though the Celebrant is a baritone role and I’m a tenor.

Here’s a picture from the San Jose Mercury News showing the chorus in rehearsal in Santa Cruz, with me in the upper left corner:

This is a small stage shot of the bows, taken from a refrigerator magnet that the Festival distributed to supporters after that season:

So why do I love the Mass so much? Let me count three main ways.

Musical Eclecticism

If there’s a type of Western music that you could write in 1970, it’s probably in Mass. You have traditional classical / opera / musical theater writing, electronic music broadcast over a quadrophonic system, pop music, rock music, gospel, blues, jazz, marching bands, and twelve-tone music all side by side. All are filtered through Bernstein’s sensibilities. Some perceive this as watered-down or pallid. I see it as a brilliant composer integrating as many different sources as possible into the ultimate statement of breaking down musical barriers between high and low, classical and pop. This is far from the only Bernstein piece to do this, but nothing I know of takes it out there as far as Mass.

This was not a popular thing to do in 1971. Classical music in academia was still largely beholden to serialism and not friendly to tonality. Rock music was still viewed at odds with classical music, a year or two before the progressive classically influenced bands became really popular. Producing this type of work for such a high profile commission was an act of artistic bravery.

The Questioning Spirit

The questioning, Jewish spirit behind the Mass is especially seen in the additional texts by Stephen Schwartz and Leonard Bernstein. Some of the more overt Jewish-ness comes out in a joke about the Trinity, a sceptical take on confession, or changing into Hebrew for the Kaddish.

For me, the ever-increasing challenging of the Celebrant by the Street Chorus seems to come straight out of the ever-questioning, interpretive spirit of Judaism. It naturally also reflects the confusion and searching of a tumultuous time in United States history, with a country intensely divided over the war in Vietnam and hippie youth culture.

The questioning starts off internally, during the Confiteor:

If I could, I’d confess

Good and loud, nice and slow

Get this load off my chest

Yes, but how Lord, I don’t know

It intensifies during the Gloria:

And now, it’s strange

Somehow, though nothing much has really changed

I miss the Gloria

I don’t sing Gratias Deo

I can’t say quite when it happened

But gone is the… thank you…

It first becomes accusatory in the Gospel-Sermon:

God made us the boss

God gave us the cross

We turned it into a sword

To spread the Word of the Lord

We use his holy decrees

To do whatever we please.

We then see rejection in the Credo:

I’ll never say credo

How can anybody say credo

I want to say credo…

It all comes to a head in the Agnus Dei. While the Choir sings the Latin text to tremendously swinging music, with great emphasis on the “Dona nobis” of “Dona nobis pacem,” the Street Chorus directly confronts the Celebrant:

We’re fed up with your heavenly silence

And we only get action with violence

So if we can’t have the world we desire

Lord, we’ll have to set this one on fire.

In our Cabrillo production, Douglas Webster had several members of the Choir join in this confrontation by stepping out of the choir at the back of the stage and joining in the gyrations of the Street Chorus on the main stage. I was one of those Choir members and it was an incredibly intense experience. We then had to freeze for 13 minutes while the Celebrant goes through his “Things Get Broken” mad scene, until the Communion finale which offers some hope – maybe – of reconciliation.

Bringing Musical and Lyrical Message Together in Theatre

The way that the music and lyrical messages reinforce each other would take something much longer than a blog post to illustrate. Bernstein does this in a theatrical context and you really do need to do this as a theatre piece to pull it off completely. A stand-up-and-sing concert version just isn’t going to make the full impact. Neither will a recording, but for most people that is the best opportunity available to experience this music. I think Marin Alsop’s recording with Jubilant Sykes and the Baltimore Symphony Orchestra is the finest I have heard.

I’ve had the great privilege of having sung Bernstein’s vocal music with two of the conductors most associated with Bernstein and today: with Marin Alsop for Mass and Michael Tilson Thomas for Chichester Psalms. I am filled with gratitude for being in the right place at the right time to have that happen.

Thank you so much, Leonard Bernstein, for all you have given us. Your compositions, your recordings, your videos, lectures, and books, and your progeny both biological and cultural have all enriched us in immeasurable ways over the years. I am confident they will continue to do so for long into the future.