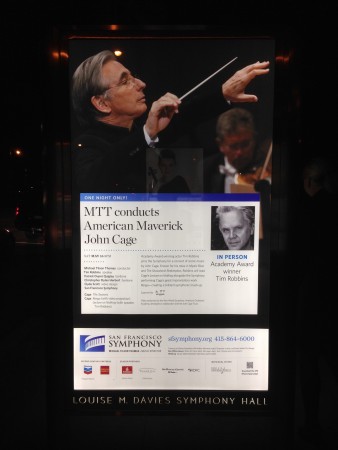

Saturday night was another example of the great golden age we are enjoying in San Francisco with Michael Tilson Thomas and the San Francisco Symphony. For this one night only, there was an amazing all John Cage concert that was absolutely stunning.

Saturday night was another example of the great golden age we are enjoying in San Francisco with Michael Tilson Thomas and the San Francisco Symphony. For this one night only, there was an amazing all John Cage concert that was absolutely stunning.

The concert started with Cage’s early ballet The Seasons from 1947. This is a very pleasant piece, completely notated without chance procedures. But if this were the summit of Cage’s invention, he wouldn’t be remembered like he is today. MTT introduced it with an apt analogy – listening to The Seasons is like going to an art museum and seeing the early, more realistic, less abstract paintings by artists like Kandinsky and Mondrian.

After intermission came the main event: Cage’s Renga from 1976. In this piece the musicians are invited to interpret snippets of Henry David Thoreau line drawings musically, using whatever means they like, according to predetermined register, dynamics, and timeline. What comes from this tends to be what MTT described as a “rainforest” of sound.

By itself that might not be so interesting for an extended time. But Renga can be performed simultaneously with other works. As a US bicentennial commission, it was originally performed together with Apartment House 1776, a work for four vocalists performing in four different American musical traditions as part of a “musicircus.” It was MTT’s genius idea to instead pair Renga with a wide variety of Cage compositions from throughout his career, in addition to videos designed by Clyde Scott drawn from popular culture throughout Cage’s lifetime. The additional works were:

- Lecture on Nothing (1950) performed by actor Tim Robbins

- Sonata for Clarinet (1933) performed by Carey Bell

- A Room (1943) performed by Marc Shapiro on prepared piano

- Suite for Toy Piano (1948) performed by Peter Grunberg

- In a Landscape (1948) performed by Douglas Rioth on harp

- Cheap Imitation (1969) performed by Edwin Outwater on piano

- Child of Tree (1975) performed by Tom Hemphill on amplified cactus (!)

- Litany for the Whale (1980) performed by baritones Patrick Dupré Quigley and Christopher Dylan Herbert

- Ryoanji (1983) performed by Tim Day, flute; John Engelkes, contrabass trombone; Stephen Tramontozzi, double bass; and Jacob Nissly, percussion

- Hymnkus (1986) performed by Mariko Smiley, violin; Amos Yang, cello; and Stephen Paulson, bassoon

- And a last-minute addition, Haiku, performed by Michael Tilson Thomas on piano from a manuscript left to him by Lou Harrison.

The contrasts and overlaps between these sources and the delightful musical and sonic material of both the parts and whole made for an exquisite performance. I couldn’t really distinguish the ensemble pieces so much from the overall Renga since the performers were seated together with the rest of the orchestra. The other soloists were distributed around the periphery of the orchestra and in the tier above the stage where the chorus sings, providing better spatial separation for both ear and eye. Screens above either side of the stage showed different videos. It was quite the musicircus indeed!

What really lifted it into genius was to perform Renga together with excerpts from the Lecture on Nothing, a key writing of John Cage’s musical philosophy included in his classic collection Silence. I read this book as a student and the Lecture contains some of my favorite Cage-isms:

I have nothing to say and I am saying it and that is poetry as I need it.

Noises, too, had been discriminated against; and being American, having been trained to be sentimental, I fought for noises.

Slowly, as the talk goes on, slowly, we have the feeling we are getting nowhere. That is a pleasure which will continue. If we are irritated it is not a pleasure. Nothing is not a pleasure if one is irritated, but suddenly it is a pleasure, and then more and more it is not irritating.

If anybody is sleepy, let him go to sleep.

Apparently, performances that include Lecture on Nothing often use John Cage’s taped voice. I’m sure that’s fine, but I really enjoyed hearing Tim Robbins read it. His actorly skills captured Cage’s wit and much of the vocal cadence without simple mimicry. It was a wonder to behold.

Whatever you want to call it – static, nonlinear, meditative, living in the moment – there is a whole range of Western music that doesn’t “go anywhere” but invites you to listen in the moment. This can be art music with Asian influences like that by Cage, Hovhaness, or Harrison; pop music like the long jams on songs by Stevie Wonder and Prince, or Van Morrison meditative songs like “In the Garden”; minimalist music; and whole swaths of jazz and new age music. Cage is a great celebrator and philosopher of this style of music. I very much like music with narrative and direction (I better, since I perform a lot of symphonic and opera music), but I like this music too.

I also like being able to listen to anything as music, like the typing of the keys as I write this post, accompanied by the quieter hums and sounds within the house, such as the refrigerator running in the kitchen next to the study. Cage really helped open my ears to that type of listening.

My introduction to John Cage was pretty unusual. Our local underground rock station, WABX in Detroit, played some excerpts from Indeterminacy one night, and I had to learn more. I found Silence in a library (at Interlochen? at MIT? I can’t remember) and things were never the same after reading it.

So thank you, thank you, thank you to Michael Tilson Thomas, the San Francisco Symphony, Tim Robbins, and all the other great soloists for a wonderful celebration of John Cage’s work in a most memorable concert. The concert was so good it got me blogging again for the first time in eight months!